Reflection on Summer 2012 Independent Study

Designing Design: The Process and Product of “Getting” Basic Writing Course Content

Teachers use the word “design” so freely to describe the process and product that results in a course outline that it deserves a closer look. As a noun, design is a passive product, to be admired yes, but not truly appreciated as the dynamic force that can be. As a verb, on the other hand, design has movement; it changes form and it experiments with mediums; it breathes emotion and intelligence. “Teacher are designers” is the short, opening sentence to Understanding by Design, by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, that juxtaposes the difference between the noun and the verb forms of the word “design.” The authors clarify that they don’t intend for their templates for course design and assessment to be a passive, paint- by- numbers formula, but rather as a dynamic tool for discovery and creativity. I must divulge that at times during the process I fell into the trap of just filling in the blanks, but then quickly realized that by taking short cuts the results suffered. The purpose of this course design project is to create a dynamic, student-focused basic writing course that fulfills institutional standards, clearly and effectively teaches and fairly and consistently assesses transferable, interdisciplinary educational skills that reflect valuable habits of mind, while also expressing and examining my own individual teaching style, including the use of website technology. The goal was to distill and apply what I have learned thus far in my studies about the various aspects of writing pedagogy and content delivery and to identify my own strengths and weaknesses in these areas in order to become a better teacher.

The foundation of course design, what to teach, how to teach it, and the assessment of learning, usually starts with institutional and departmental standards including a more recent focus on interdisciplinary and transferable skills. Erika Lindemann, in A Rhetoric for Writing Teachers, however, previews her discussion on writing course design with an even more fundamental question; is the course to focus on the expressive nature of the individual writer, or on students as members of a discourse community in which “the teacher deliberately fosters collaboration so that the students must help one another learn and may share in the group’s achievements” (261)? Lindemann might resist Wiggins’ and McTighe’s suggestion that teachers jump in so quickly, to begin the design process by first isolating the nouns and verbs in course standards, and to define immediately the “big ideas” and “core tasks” on which all other aspects of the course hinge. I must say however, that having deliberated on the theoretical discussions of Lindemann and others and deciding that collaborative learning is the way to go, by using Wiggins’ and McTighe’s method, I was able to fairly quickly and efficiently condense five wordy statements into one tightly packed course objective: “Students will develop writing and critical reading skills that are transferable across disciplines and relevant to an engaged academic, work, and community life.” Something about Lindemann’s personal and empathetic teaching style reminds me of Mina Shaughnessy’s realistic goal to reduce rather than eliminate writing errors and thereby foster confidence and self esteem in basic writing students. For Shaughnessy, in 1970, at the dawn of college open admissions policy, teaching and assessment of basic writing is all about creating confident students by concentrating mainly on prescriptive grammar instruction assessed holistically. Although Shaugnessy’s goal to reduce sentence-level and paragraph error is vital, for my purposes, the broader assessment goals of Wiggins and McTighe are more transferable and analytical, especially conducive to my goal of a collaborative, discourse community.

Whatever basic writing assessment focuses on, whether grammar or content, the criteria must be clear, effective, and consistent, so that students know what is expected of them and how they will be graded. Wiggins’ and McTighe’s rubric matrix, based on their “Six facets of Understanding,” encourages continual assessment of student learning. The six facets state that as evidence of true understanding of what’s been instructed, students will be able to:

- explain

- interpret

- apply

- empathize

- have perspective

- and have self-knowledge

Creating analytic rubrics using any method is time-consuming, but they encourage teachers to reflect on how clear and effective their assignments are. Deconstructing an assignment for the purpose of assigning assessment categories can be accomplished several ways including, reflecting on one’s goals and purpose, gathering evidence from previous assignments, or designing collaboratively with students. The reflective process advocated by Dannelle Stevens and Antonia Levi in their book, Introduction to Rubrics, which involves asking what and why questions about the purpose and course context of the assignment was especially helpful to me as a pre-service teacher. Reflective questions evolve smoothly into a list of assignment objectives to use as assessment criteria. Like Wiggins’ and McTighe’s suggestion to use course descriptors to create goals, Anson and Daniels similarly encourage the use of the course description to define rubric categories, cautioning however, that “the greater the number of categories, the more complex and time-consuming the grading” (Roen 393). One experienced teacher I spoke with resists rubric grading altogether, believing that to put student writing into “boxes,” especially when categories are narrowed down for time purposes, is unfair and incomplete. While I respect this teacher’s knowledge and skill, I would question my ability to be consistent using holistic assessment.

Proponents of analytic rubrics argue that although “for beginners . . . the first few rubrics may take more time than they save . . . This time is not wasted”(Stevens and Levi 14) because a well prepared rubric is equally conducive to classroom success for both teachers and students. Since grading is one of the areas where new teachers feel least prepared, using rubric templates on websites such as Rubistar is an even more efficient option while gaining classroom experience. But, experience is at the base of rubric creation using the Understanding by Design method. Wiggins and McTighe use samples of student writing to define traits that represent categories and performance levels. They are adamant that “a rubric is never complete until it has been used to evaluate student work and an analysis of different levels of work is used to sharpen the descriptors” (180). While the “Six Facet Rubric” is effective for experienced teachers and gracefully incorporates more subjective aspects of understanding including habits of mind into the mix, for a pre-service teacher like myself, it became increasingly complicated to translate those ideals into words. I finally designed a sample rubric for one assignment by borrowing ideas from different sources, including Understanding by Design. Optimally, I would like to collaboratively build assignment rubrics with my students for most assignments.

Including students in the assessment process builds their confidence by clearly defining expectations and reinforcing responsibility for their own learning. I was concerned, however, that basic writers might be overwhelmed if asked to produce a rubric at the beginning of the semester, so I opted to have students contribute to the rubric for the simpler, presentation portion of the second major assignment, the career exploration project, as their first attempt. During the final research assignment, designing the rubric will begin with the introduction to the assignment and will be revisited during the next few class periods to be refined as needed. This process will allow me, as a beginner, to get to know and grow along with my students, to assess the different levels of knowledge they have of the course material we’ve covered thus far, and also assess the clarity and effectiveness of my assignments.

Both Lindemann and Shaughnessy stress that it’s not only important to have clear and effective course goals, writing assignments, and fair and effective means of assessment, but also to understand the intellectual and emotional needs of adult basic writers in order to determine course tone and content, and the resources and support systems needed for each individual student. For students, “grade points are currency” and assignment tasks need to be pertinent to life outside the writing classroom. This transferability of knowledge and skill informed my choice of the American workplace as the theme for my basic writing course design project. Shaughnessy reminds basic writing teachers that “the aesthetic that dominates English teachers’ judgments has generally been shaped by years of belletristic literature, and the pleasure in the arrangement of words” leaving students to define acceptable college writing a “writing you can’t understand” (196). This type of thinking doesn’t result in “currency” that students can “spend” in their daily lives. Citing Kenneth Burke, Lindeman paraphrases his description of rhetoric as “a function of language that enables human beings to overcome the divisions separating them” (53). This statement describes the purpose of basic writing classes as social currency that “[connects] to the social fabric of the culture in which they occur” (54). Students, therefore, should be encouraged to write clearly and simply, with attention given to writing for specific audiences in an appropriate way, and basic writing teachers should consider texts and design assignment tasks that reflect real-life situations.

The autobiography assignment unit allows the expressivist in the student to surface while beginning to address thought processes used to explore topics, essay organization and structure, using resources such as handbooks and online tutorials to self-correct mechanical errors, and the peer review process. Although writing autobiography strengthens narrative skills that can later be used in resume and letter writing, my primary purpose for the assignment is to build confidence and self-esteem by having students write reflectively about their own history. During this initial unit, I will set the tone for the class by introducing the Values Analysis which is adapted from an example on the Council of Basic Writing Resource Share website. I adapted it to focus on habits of mind included in the Council of Writing Program Administrators “Framework for Success in Secondary Writing.” The autobiography assignment is the student’s chance to identify and reflect on values that inform their lives and how those values impact their educational and career paths. Another activity I plan for early in the semester that meshes well with the Values Analysis and the autobiographical essay is a class video that will be an informal, autobiographical sketch about students’ initial thoughts, concerns, and fears about their writing and this class; we will review and comment on the video on the final day of class ― hopefully in good humor. After making the video will be the opportune time to form the small, static groups, which will be based on student’s similar occupational goals and interests and will reinforce the collaborative goal for the remainder of the class. Forming relationships in small groups will create a feeling of safety, community, and mutual responsibility in the classroom. Initially, these groups will do some in-class activities together, then, after a peer review orientation session, students will enrich their learning experience by assessing one another’s writing.

Following the autobiography assignment will be the career exploration assignment. Like the autobiography assignment, the career exploration project will begin with an explanation of how this assignment teaches skills that fulfill the main course objective, how the assignment scaffolds on the previous one, and how it teaches skills that will be used for the final, research essay. The assignment is based on Duerden, et al’s “Profile Assignment” for engineering students, designed by the authors after they realized that students had little actual knowledge of the occupation they had chosen to pursue. The scope of the career exploration assignment is broader, taking five week to fully complete. The assignment is an especially dynamic design integrating various types of research: interviews, web searches, traditional and online library research, two oral presentations, a mini-library tutorial based on the Perry Library’s research tutorial resources, and a career fair role play presentation. Students will have the opportunity to use online mapping tools to outline their essays, and they will be encouraged to enrich their career fair presentations with images and other graphic design elements. Class time will be used to target important issues related to research, integrating sources and avoiding plagiarism, and improving writing sophistication through sentence combining and enhancement techniques. These will be hands-on, collaborative activities; lecture will be kept to a minimum. We will read from Studs Terkle’s Working, emphasizing its theme of American work life, past, present, and future and discuss how it incorporates the use of autobiography, research, and reporting, while it connects the audience socially and culturally to the subjects.

The unit design for the career exploration project focuses on using class time to the best advantage with emphasis on building student confidence through group writing activities, oral presentations, and reading aloud. Students will practice writing in nearly every class, whether working on their own texts, or responding to peer writing. In this way, they will acquire the tools to demonstrate their learning. Organizational skill will be acquired while juggling various tasks in order to complete the assignment effectively and efficiently. Wigggins and McTighe emphasize the importance of “constant movement back and forth between whole-part-whole and learning-doing-reflecting” to sequence activities in the best organizational context (220). This was probably the most difficult part of the unit design, what to add, what to leave out, and continuing to address Framework values while moving on to the next assignment. For this reason, and since the completion of the career exploration projects fall roughly at mid-term, I felt that this would be a good time to conference individually with students about their strengths, weaknesses, and concerns (and to reflect on mine) as we move into the final major assignment. The three major assignments for this basic writing class are scaffolded in several ways; by difficulty, mainly length of essay; by types and degree of research required; by formality of vocabulary, based on a specific audience; by level of cross-curriculum and workplace transferability; and each is closely tied to the main course objective.

Another major component of my objective to teach “skills that are transferable across disciplines and relevant to an engaged academic, work, and community life” involves content delivery; how students “get” my course material. Let’s go back to the discussion at the beginning of this essay for another look at how word meaning reflects more broadly in course design. For instance, the word “get” has both physical and mental components. First, how do my students physically grab onto all of the material my course contains: syllabus, calendar, lesson plans, announcements, grades, contact information, etc. Most important in this area is that students have access to the material at all times, that the material is well designed, and that it is complete. Second, how do my students “get” or understand what the content hopes to deliver. Melding the two “gets” requires that I speak the student’s language and that they understand mine; theirs being the language of technology natives, and mine being the language of a technology immigrant, realizing also that these categories usually overlap.

The first communication my students will have with me, and therefore, their first impression of me as a teacher and as a person, will be through the course website. Setting the tone of my language to appeal to my student audience is my primary concern. The homepage of the course website is my first teaching moment, so I seize the opportunity to talk a little about my thoughts about writing and student writers, using a tone that is both friendly and professional. The hook is the short quiz/poll on the introduction. What I hope to accomplish by including this quiz/poll is to have students understand that I believe that every moment is a teaching/learning moment. Each time students visit the site, the homepage will remind them of the question “what is good writing?” The subtitle reminds them that they are “writers under construction,” that they are not “empty vessels,” that they bring a foundation of knowledge with them; my job is to provide tools and a blueprint.

The blueprint of a course is the syllabus, containing the institutional formalities, such as the academic honesty and disability policies, but also containing information such as the main course objectives and classroom policies that are important to students’ success in the course. The syllabus is located second from the top in the vertical navigation bar on the left side as a reminder of its importance. I picture the syllabus much like an “employee handbook,” important, but seldom referred to after the first day unless there is a problem, therefore, it’s important that it be readily available and prominently displayed. For better readability, I’ve made it as short as possible, with links to official policies, buttons to other course site pages, and with images to draw attention to important points. By placing the grading policy at the bottom of the page, students will be encouraged to at least give the rest a scan.

The most useful components of hypertext course websites are, for students, the ability to connect quickly to the information they need most urgently in a logical, but non-linear way, and for teachers, the ease of creating a basic class site. Each assignment can have its own link, and all handouts, readings, checklists, etc, can be accessed within the assignment; each can be quickly and easily changed if needed. I used six main pages, three assignment subpages with eight tertiary pages, and eighteen links to various other websites to create my course site design. In a fully-functional course design, I would have individual links to each class unit so students would know exactly what we would be working on each class period. I have used WordPress and Google to create other websites, but I wanted to use an application that I hadn’t used before, so I chose Weebly. I learned to use the program just by a watching and reading the tutorials on the site. I used the free program which didn’t have all the options of the professional program, but it allowed me to do most of what I wanted to do except embedding videos and PDF files. I especially liked how easy it was to manipulate and layer images with the free Weebly program. All of the images I used on the site were manipulated in some way, either by changing the color or opacity, or by cropping or rotating the image. If I was to do anything differently, I might choose another design template because I would have preferred a different background color on my site, but the free Weebly application doesn’t allow you to change colors. Although I will become naturally more proficient with the technology as I experiment further, overall I feel that I met my goals of a clear and accessible class website that I hope will be as enjoyable for students to use as it was for me to create.

We learn best by doing, taking ideas and using tools and blueprints to construct a well designed, solid, aesthetically pleasing, and dynamic structure or product; this is what we teach basic writing students, and this is how teachers should approach course design. What this process taught me is that I will always be a student; gleaning knowledge and ideas through texts, from students and colleagues, and through my own curious nature. This means that not only will my course designs change, but my teaching style and philosophy will evolve as my toolbox fills with experience and skill. I have learned four things so far about my personal style while designing this course that I hope to pass on to my students through my teaching; one, I believe life is a conversation, not a lecture; two, I hold personal responsibility in high regard, you have to do the work; three, that I can be nurturing and still have a tough shell, that standards shouldn’t be compromised; and four, that the project is never finished. I’ve also learned that regardless of our ideals, values, and skills, it is essential that we critically assess our strengths and weaknesses in order to grow. Strong points that I discovered about myself as I constructed this course design are; my ability to connect with and show empathy for others though my writing style; my ability to motivate others through personal example, the reason behind the links on the teacher’s page; and my ability to take an idea and run with it. The last point emerged as I visualized scenarios for my project prompts. I found I could easily express an entire process from beginning to end as a script that was not only helpful to me for designing and sequencing units, but that will hopefully engage my students and spark their creative imagination. Areas that call for improvement, on the other hand are; my difficulty in letting go when something is clearly not working, this is a big time waster; estimating time for and prioritizing class activities, I could always imagine my plans being derailed; and the need to discover best practices based on twenty-first century literacy skills, the best reason I know for attending conferences and being otherwise engaged with colleagues. In closing, like Wiggins and McTighe insist in their estimation of the recursive nature of rubrics, a course design, no matter how well designed, is never complete until it has been evaluated in the classroom.

Cited

“Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing.” Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and the National Writing Project. 2011. Web. 6 Aug. 2012.

Lindemann, Erika. A Rhetoric for Writing Teachers. 4th ed. New York: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

Roen, Duane, et al., ed. Strategies for Teaching First-Year Composition. Urbana: NCTE, 2002. Print.

Rubistar.com. ALTEC at U of Kansas. 2008. Web.

Duerden, Jeanne Garland, and Christine Everhart Helfers. “Profile Assignment.” Roen 152-164. Print.

Kyburz, Bonnie Lenore. “Autobiography: The Rhetorical Efficacy of Self-Reflection/Articulation.” Roen 137-150. Print.

Shaughnessy, Mina P. Errors and Expectations. New York: Oxford UP, 1977. Print.

Stevens, Dannelle D. and Antonia J. Levi. Introduction to Rubrics. Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2005. Print.

Wiggins, Grant, and Jay McTighe. Understanding by Design. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2005. Print.

Weebly.com. Weeby, Inc, 2012. Web.

There’s Time Left for Teaching

A colleague of mine recently suggested that because of all the important areas to be covered in basic writing classes, grammar, punctuation, vocabulary, plus giving attention to the actual writing process, class size should be limited to ten students. In an ideal world this would certainly be the case, but it’s highly unrealistic in today’s economically strapped schools. The actuality is that basic writing class size varies widely among colleges and universities. Given the finite time resource and the growing expectations placed on teachers to address individual student’s needs and foster transferable knowledge and skills while improve writing test scores, how do writing teachers determine what areas to concentrate on to use class time to the best advantage?

When creating a class schedule, after allowing for institutional holidays and professional enhancement activities, etc., the juggling game truly begins. On the one hand, student’s individual needs must be addressed, and on the other hand, institutional and course objectives are expected to be met by all students regardless of prior writing experience. Mina Shaughnessy, in Errors and Expectations, produces page after page of examples for addressing various common grammar and punctuation errors that plague basic writers, but she places much of the responsibility for correcting those errors on the student. The teacher’s role, according to Shaughnessy, is to point out error patterns and offer solutions for self-correction, allowing the student to see that “although he has twenty errors he has only five problems” (127) which can be corrected through the use of handbooks, handouts, and other tools. Relegating more responsibility to students for the self-correction of their work allows teachers to maintain high expectations for student writing by utilizing class time for more writing practice.

Along with high expectations for the traditional aspects of writing such as spelling, grammar, and punctuation, comes today’s emphasis on twenty-first century literacies, the ability to produce text s that engage the student in a participatory discourse community. These types of skills can be time consuming to introduce and hard to measure; they may also be counter-intuitive in American society where individuality is stressed. The reward for including these frameworks, however, is a more reflective and creative learner prepared to do well in other college classes as well as on the job. Because writing classes structured around collaborative projects that address student’s real world needs and concerns are best at producing meaningful and transferable learning and skills, traditional lecture-based classes may be becoming obsolete. Creative use of class time including collaborative activities requires many hours of preparation for the teacher, but might be offset by student self-assessment and peer review activities.

Given that there must be a trade-off between time allocated to the rudiments of the writing product and the creative reflection of the writing process, even Shaughnessy acknowledges that making writing better isn’t necessarily making it right. Teachers, therefore, are charged today with setting goals that are both attainable and relevant in an economically, racially, and culturally diverse society. The challenge is to constantly self-reflect on individual teaching practices and to refine student assessments in able to fine- tune course content and also to continue to encourage institutions to acknowledge the importance of class size for the success of basic writers.

How Do You Spell “Big Picture”?

I have always had difficulty with spelling, so I was relieved to learn, while reading chapter five of Errors and Expectations that some college instructors also confessed to this deficiency. Shaughnessy reassures us that poor spelling is not the sign of a lack of intelligence, but I already suspected this of my colleagues; haven’t we made it to, or through, graduate school, for heaven’s sake? The bad news she says is that it’s harder for adults to learn to spell. That’s what I like about Shaughnessy; she has a “this is the problem, and this is the solution” attitude about basic writing topics that baffle many of us. She has a knack for prioritizing, observing, and then dissecting the most complicated writing error issues and then offering a recipe for improving the outcome.

The main problem, she says, is poor preparation for writing; we learn to spell by seeing, hearing, and writing words in our younger years. Is learning really, as Shaughnessy claims, more difficult as you grow older? Naturally, I was intrigued by this observation that concerns not just me, but everyone over forty. It turns out that it is more difficult to learn new information as we get older, but complex learning that requires synthesizing information, which is important to academic writing and thought, actually improves:

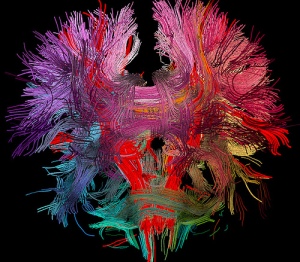

The brain, as it traverses middle age, gets better at recognizing the central idea, the big picture. If kept in good shape, the brain can continue to build pathways that help its owner recognize patterns and, as a consequence, see significance and even solutions much faster than a young person can. The trick is finding ways to keep brain connections in good condition and to grow more of them (Strauch).

Though my brain is a complicated map created from a lifetime of thought connections, I find that I need to make lists and maps of all kinds. So, I like Shaughnessy’s suggestion for making error and vocabulary lists, but I also thank the gods for spell check.

Cited:

Strauch, Barbara. “How to Train the Aging Brain.” New York Times, 29 Dec. 2009. Web. 21 June 2012. Link.

A Scientist Debates a Pollyanna: No Easy Consensus

Slideshare presentation by Sharon Salyer

The ongoing debate about and the frustration surrounding the unpreparedness of students for post-secondary education seems no closer to resolution. In economic terms, the answer would seem to be that, yes, society could save a lot of money by detouring underperforming students toward vocational/technical schools. On the other hand, besides preparation for a career, higher education offers many intangible benefits as well, such as increased critical thinking skills, cultural awareness, and improved communication skills, all considered to be critical illiteracies in the twenty-first century. But, can a few years of post-secondary education make up for a life-time of societal and educational neglect?

Patricia Cross (McAlexander 2000) seems to be saying that, no, it would be more realistic and humane to steer under -achieving students toward their own level of success― spare them the disappointment of failure. Many would agree, and none can deny that many families of the nineteen fifties and sixties prospered with even less than high-school educations. In the long run though, there are many more ways that societies as well as individuals with less education lose out. The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement finds that higher education results in these key indicators of a successful society:

• regular volunteering for non-political groups,

• active membership in any groups,

• raising money for charity,

• working with others on community problems,

• membership in political groups,

• regular voting,

• contacting officials,

• signing e-mail or paper petitions,

• and being “hyper-engaged” (involved in at least 10 different activities).

Higher education seems to be the rising tide that raises all boats, but a surprising, secondary indicator of economic success is the educational level of mothers. Although there are many other variables involved, like family stress and parental involvement, this indicator seems to hold true for Shaughnessy, whose father only had a grade-school education, but whose mother held a teaching degree.

Mina Shaughnessy had the capacity to feel what it’s like to walk in someone else’s shoes ― empathy. She isn’t surprised by Basic Writing student’s “ambivalent feelings about ‘making it’” because of their many previous failures. But, motivation, one of the reoccurring reasons cited for underachiever’s lack of success, is paradoxically, precipitated by success. Few of us would remain motivated without the occasional success. Without educational success, especially the ability to write well, when we move out of the hypothetical into the real work-a-day world, she reminds detractors that

a person who does not control the dominant code of literacy in a society that generates more writing than any society in history is likely to be pitched against more obstacles than are apparent to those who have already mastered that code (13).

The problem I have with Shaughnessy is that her empathy with students sometimes verges on condescension, much like Harriet Beecher Stowe, the writer of one of my least favorite classics, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Like Stowe’s novel, however, the empathetic and emotional tone of Shaughnessy’s writing moved many people to action. Other educators may also object to Shaughnessy’s mantra because her Current Traditionalist beliefs ooze conformity and ideology (Bloom 1996, Foley 1989).

As we’ve become a more culturally diverse and inclusive society (at least on the surface), there is another progressive linguistic movement that says that all language dialects should be valued and preserved. Reconciling these various beliefs requires ongoing dialog between empathetic educators. Until a consensus is reached, we must aim to educate all students as if they were members of our own families.

Cited:

McAlexander, Patricia J. “Mina Shaughnessy and K. Patricia cross: The forgotten debate over postseeondary remediation”, Rhetoric Review, 19:1-2 (2000): 28-41. Web.

On Shaughnessy, Syntax, and Students

The introductory chapter of Mina P. Shaughnessy: Her Life and Work by Jane Maher is filled with so much emotional energy that it threatens to chase off the timid graduate student preparing to teach composition in community college. Faced with the new policy of open enrollment in New York City, in 1966, Shaughnessy was tasked with creating a basic writing program that was inclusive of all the dialects and writing ability levels of the previously underserved students of poor and immigrant New York City neighborhoods. Ever a politically charged issue, in 1998, New York mayor Giuliani wages war against what he sees as a waste of money and class space. Cynthia Lewiecki-Wilson and Jeff Sommers, in their article “Professing at the Fault Lines: Composition at Open Admissions Institutions,” paraphrase the attack:

Incoming students who do not pass gateway placement exams in reading, writing, and math will be barred entrance, ending the open admissions policy established in 1970. During this public campaign of ridicule, confusion and duplicity abound as the mayor first attacks the community colleges, then the senior colleges. No one is quite sure what will happen at the city’s community colleges . . .

Currently, open enrollment is policy in Virginia’s community colleges, and once again controversy simmers over the poor quality of college writing. Nobody seems happy, teachers are demoralized because they are “torn between their knowledge that teaching writing is important and challenging the harsh public voices attacking their enterprise” (442). I must admit that I too have been noncommittal about what environment I believe is best for teaching BW courses that sometimes don’t carry college credit, use up tight funds, and often result in students never graduating. The cost to students is more than economical though; their dreams are often shattered. I questioned a while back when a student I was tutoring at Tidewater Literacy was accepted into the local community college, but I also knew that this student had goals that wouldn’t be met by the rudimentary reading assignments TL’s adult literacy curriculum espoused. Besides, learning doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Education is cultural and participitory, requiring the embedding of habits of mind as well as academic skills, so I’m gratified to find that there are many teachers today equally as committed as Shaughnessy was back in 1966 to finding new (and old) ways to reach Basic Writing students in college. I hope the changes that are now taking place, combining the reading and writing programs, defining twenty-first century literacy skills, among others, will do teachers and students justice.

Errors and Expectations, written before computer classrooms were a reality, is still relevant for its skill at confronting another, still controversial issue; grammar correction. Shaughnessy, however, confronts both grammar correction and the nay-sayers who think teaching writing process is “a little soft” by pointing out that even though grammar errors are plentiful and therefore shouldn’t be ignored, there are discernable patterns of error in most basic writing that are explainable and manageable. Shaughnessy’s point that “the issue is not [the student’s] capacity to master the unfamiliar forms of formal English . . . but to write,” emphasizes voice over code. The four most important syntax issues she recommends addressing with BW s are:

- Sentences

- Inflection

- Tense

- Agreement

Shaughnessy also places a lot of responsibility on students to self-correct grammar errors through the use of handbooks and handouts chosen for specific problems so that the writing process can remain the dominant focus of class time. This is the approach I would like to take to teaching grammar as I develop my Basic Writing course outline. The key issue will be how to assess grammar and mechanics as an “important to know” rather than a “core task.” This may be one of those areas where Dr. Phelp’s (2012 ODU Faculty Summer Institute) suggestion for daily quizzes might come in handy – maybe a cell phone quiz would work.

Cited:

Bowler, Mike. “Dropouts Loom Large for Schools.” Retrieved from www.usnews.com

Maher, Jane. Mina Shaughnessy: Her Life and Work. Urbana: NCTE, 1998. Web. URL

Open Admission. Retrieved from The New York Times Article Archives. URL

Shaughnessy, Mina P. Errors & Expectations. New York: Oxford UP, 1977.

Understanding, Knowing, and Doing

This week I’ve been contemplating the difference between the words “understanding, knowing, and doing” in a course objective template I’m using, and the implications of those differences in how course standards are written and interpreted. Taking a Constructivist viewpoint, I have also identified words that signal key objectives in a typical, community college course standard in order to work toward a successful, student-centered model of a first-year writing class, structured on the book I spoke about last week, Understanding by Design. How key words are interpreted become the basis for a robust course outline.

Understanding is defined, in Understanding by Design, as the long-term and transferable goal that drives true learning. What we thoroughly understand stays with us as a building block for future learning that transposes itself over time and space. If, for instance, a person learns that there are numerous ways (and no single right way) to approach a problem; that as an individual, his or her creative process may be different from someone else’s; that his opinion is valued; and that her first attempt is only practice, that person is well on their way to becoming successful in school, at work, and in life.

Unfortunately, many students arrive in college writing classrooms with a more ingrained understanding― that they can’t write. Even though they effectively communicate verbally with family, peers, and employers on a daily basis, emphasis on “correct” writing has devalued not only students’ writing products, but also their language codes and social cultures (Shaughnessy 92). One can certainly see that by making a long-term goal that is seemingly both unneeded and unreachable; little motivation to succeed will result. With broad, transferable goals and deep understanding of the purpose and process of writing, hopeful teachers believe that, given the right tools, even basic writing classes can confer an acceptable level of success to each student.

Knowing is the word used in Understanding by Design to identify the attainment of skills required to accomplish a task or solve a problem. Teachers, of course, can’t guarantee that all students will become excellent writers, but they can provide the necessary tools for each student to do their best. The basic skills needed for proficient college writing that Mina Shaughnessy discusses in her 1977 book, Errors and Expectations, including handwriting, punctuation, and spelling, are still recognized today by experts Henry Jenkins and the Carnegie Corporation as essential. Along with the basics, however, there are new technological skills, social skills and ethical frameworks that are necessary for students to function in today’s participatory culture. The long list of “how tos,” however, should be refined and prioritized to provide individual students with the power and self-confidence to participate effectively in school and life.

I went to college, but I learned to write by reading – and writing. Daniel Pinkwater

Doing inspires self-confidence, and practice perfects the end product. This is why many experts bemoan the lack of writing practice students are currently getting in school. Because of new curriculum reforms driven by student’s inadequate preparation for college writing, most standards will now be including more writing practice, both in writing classrooms and across disciplines. The Carnegie study linked above discusses the transferable skills developed through reading and writing. Writing, as well as reading, the authors say, “is a predictor of academic success and a basic requirement for participation in civic life and in the global economy” (3). The metacognitive skills acquired through the writing process, experts say, are equally important as the written product itself.

Cited

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). “Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools” – A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York.Washington, DC:Alliance for Excellent Education. Retrieved from http://www.all4ed.org/files/WritingNext.pdf (June 6, 2012).

Jenkins, Henry. “Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century.” Retrieved from http://digitallearning.macfound.org/atf/cf/%7B7E45C7E0-A3E0-4B89-AC9C-E807E1B0AE4E%7D/JENKINS_WHITE_PAPER.PDF (June 6, 2012).

Pinkwater, Daniel. Retrieved from http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/d/daniel_pinkwater.html

Shaughnessy, Mina P. Errors & Expectations. New York: Oxford UP, 1977.

ODU Faculty Summer Institute (and more)

Backward design is a powerful theory. While jogging along the Elizabeth River this morning with my dog Stretch, it occurred to me that backward design, a course design strategy espoused by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe in their book Understanding by Design, was evolving into a web of interconnectiveness permeating all of my thought processes this summer. This became apparent to me in several ways this week; first, as I work to turn the theory into practice by designing course objectives for several writing classes; then, during the ODU Faculty Summer Institute sponsored by the Center for Learning and Teaching; and finally, as I reflected this morning on how to order the many tasks ahead as I plan for graduation in the fall.

Synthesizing the lofty course standards for writing classes provided by institutions into condensed and prioritized goals achievable in a classroom of individuals with varying levels of abilities and aptitudes has proven to be a time-consuming, yet rewarding task for this neophyte. The recursive process began for me, after reading McTighe’s and Wiggins’ book, by reading course syllabi written by instructors at various institutions and reflecting on the philosophies of the teachers that I envisioned behind the printed words in their course objectives. Their tones ranged from poetic to mind-numbing; some even seemed threatening.

Most of these class objectives are certainly gleaned from years of experience and the desire to communicate clearly to students what the instructor intends to teach them over the course of the semester, as well as satisfy institutional standards. McTighe and Wiggins, however, suggest that by examining the nouns and verbs in the academic jargon of standard objectives, the “big ideas” and questions can more easily be turned into prioritized classroom objectives and activities that result in deep understanding, rather than just surface knowledge and content coverage. This is the goal of my summer studies and why this week’s conference was so meaningful and pertinent to me.

On Tuesday morning, Dr. Tara Gray, the keynote speaker for the Faculty Summer Institute began by encapsulating the backwards design theory into the overarching theme of the conference; a thoughtful, goal-oriented pedagogy that promotes ongoing assessment and meaningful activities over a teacher-centered lecture “performance.” She presented twelve steps to facilitate an inspiring and interactive classroom. Dr. Gray spoke like a teacher in touch with her philosophy; love your students and take responsibility for your class, and she acted like an accountant, counting each classroom second like precious gold. More important, I watched as experienced teachers around the room sat up straight, leaned forward, asked questions, nodded, and tracked her eyes attentively. In other words, they acted like we want our students to act during our classes.

Teachers are individuals just like students are, but I guarantee that as Dr. Gray moved about the room, she left a net of interconnectedness in her wake. I left that session filled with deep understanding and inspiration as well as a feeling of community with other teachers. Speaking with several teachers yesterday made me excited about graduating next semester and finally getting into the classroom. That makes how I set goals, how I organize and prioritize my tasks, and how I create meaningful, academic artifacts which culminate in a useful and reflective portfolio my major academic focus. That said, the value of deep understanding, personal responsibility, and community is my individual, life focus.

Academic and career advancement isn’t the most difficult task we and our students have to face in our society, life is. This brings me to the value of life experience in any endeavor. As we grow older, we should learn to work smarter rather than harder. As a runner, I can say emphatically that physical strength and stamina will decrease much sooner than one thinks, but I can say equally emphatically that I won’t enjoy the beauty of an early-morning river run any less. I am a life-long learner, and I hope to be a life-long runner. Will I do things the same way I did them in my youth? No, but I’ll do them more reflectively. And therein lays my secret weapon; I can not only design backwards, but I can look backwards. I have a valuable history as well as a valuable future

Wiggins , Grant, and Jay McTighe. Understanding by Design. 2nd. Columbus: Pearson, 2005. Print.

Independent Study – Contemplating Habits of Mind in the Classroom Context

Thoughts on Habits of Mind

Habits are repetitive acts that form our action and reaction patterns throughout life. Aristotle says,

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence therefore, is not an act, but a habit.

Habits of mind are learned from our environment. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick, in Activating & Engaging Habits of Mind, emphasize the use of habits of mind in the classroom and make suggestions to create a “thoughtful” environment to facilitate their inculturation. Their definition of “thoughtful” implies not only an environment of learning, but also of empathy. A “thoughtful” classroom, they say, is built around five teacher behaviors that form the acronym S.P.A.C.E.

- Silence- giving students and teachers time (3-5 seconds) to formulate responses to questions.

- Providing Data- giving students adequate verbal, written, or other resources to support successful learning.

- Accepting Without Judgment- accepting student input with a non-judgemental response style, i.e. “passive verbal acknowledgement” (“Let’s add that as a possibility”) and paraphrasing rather than ineffective praise.

- Clarifying- attempting to fully understand what the student is saying by asking questions.

- Empathizing- the teacher recognizes that emotion and learning are deeply intertwined as a unique social response to circumstances outside the classroom.

After looking at four lists of habits of mind for classrooms, I was able to synthesize three that stood out to me as reflecting the “watchwords” of Erica Lindemann’s ideal discourse community (261).

- Thinking interdependently (Costa and Kallick) — Collaboration.

- Listening with understanding and empathy (Costa and Kallick) — Community.

- Responsibility (NCTE) — Personal responsibility and group accountability.

Focus on Habits of Mind

Responsibility: Responsibility is a habit of mind that is the root of all community action; it is our responsibility to and for the society in which we live. It is also a habit of mind by which we either hold or relinquish our personal power over our circumstances. Our choices have far-reaching and cumulative effects for ourselves and those around us. Teachers and students are accountable to each other; this commitment must be clearly stated, agreed on, and upheld. This does not mean rigid adherence to rules, but actions that demonstrate mutual caring and respect.

In the long run, we shape our lives, and we shape ourselves. The process never ends until we die. And the choices we make are ultimately our own responsibility.

Eleanor Roosevelt

http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/keywords/responsibility.html#KTuuXP4etBFdEKWK.99

Teaching Habits of Mind in the Digital Writing Classroom

Responsibility – the ability to take ownership of one’s actions and understand the consequences of those actions for oneself and others. Responsibility is fostered when writers are encouraged to:

• recognize their own role in learning;

• act on the understanding that learning is shared among the writer and others—students, instructors, and the institution, as well as those engaged in the questions and/or fields in which the writer is interested; and

• engage and incorporate the ideas of others, giving credit to those ideas by using appropriate attribution.

http://wpacouncil.org/framework

Course Design

Erica Lindemann, in A Rhetoric for Writing Teachers, offers a logical course design process that reflects a “thoughtful” classroom:

- Decide on your preferred class structure. Lindemann makes suggestions and comparisons between different styles of class structure. What, or subject class style is represented by the typical lecture dominated class. Who styled classes (thoughtful classroom), on the other hand, provide a more individualized, interactive, student-centered model.

- Choose a model. Lindemann offers two models for process-based classrooms; individual/ expressive and, probably more pertinent to the class I will be helping to plan this semester, a collaborative/discourse community. The latter should be student centered and based on real-world context

- Survey your students. I like that Lindemann stresses knowing the academic interests and abilities of students in order to determine meaningful reading and writing assignments and the type of support services they will need (computer lab, written or video tutorials, detailed handouts). Here’s a link to Atomic Learning’s technology assessment resources.

- Write 5-10 goals for the class. What will students know, and what will they do in clear and simple language.

- Create scaffolded assignments.

- Write syllabus. Lindemann defines this process as “discovering the relationship between the ‘paragraphs’ or units” of the course.

- Write lesson plans. Lindemann emphasizes plan flexibility, recognizing that student’s needs supercede the class schedule. I’m glad she included an end of class questionnaire to assess: what students enjoyed, what things too much time was spent on, and what students needed more help on next class period.

Cited:

Costa, Arthur L., ed. and Bena Kallick, ed. Activating & Engaging Habits of Mind. Alexandria:ASCD, 2000. Print.

Lindemann, Erika. A Rhetoric for Writing Teachers. 4th. NY: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

ENGL 539 Portfolio Cover Letter

Throughout the course of this semester, my technological proficiency greatly improved in ways I often didn’t notice until I almost effortlessly accomplished a formerly difficult task. I have to remind myself of where I started, however, to fully appreciate this statement. Nearly all that was accomplished in the various projects for this course was a first for me. Openness the habit of mind pertaining to a willingness to think differently, was sometimes an obstacle to my learning process. I attribute this to a stubborn tendency to “go it alone” rather than seek the input of peers and experts. Happily, however, I was finally able to accomplish my main goal of learning how to create a basic, classroom hypertext website incorporating suggestions made by several classmates. The journey of expanding my technological expertise has truly been an adventure of not only self-awareness, but the realization that, as Marshal McLuhan says, “the medium is the message.”

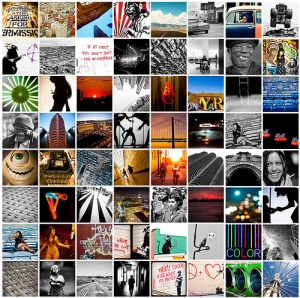

This analysis is especially thought provoking as I reflect on the importance of audience in composition and how my use of technology sends a different message to that audience than a message written on paper. Unlike a letter written in the traditional, pen and paper medium, technological communication, through an Image Project devoid of text, evokes emotion directly through one’s vision without the need of translating words. I found that this does not make communication easier, only different. Photoshop Express, the image editing software that I used allowed me to add visual “adjectives and verbs” to my photo essay . Often though, in the excitement of learning a new technique, meaning was lost or confounded. I sharpened my focus on a more specific audience to clarify details for myself and my “readers”.

Metacognition the habit of mind focused on making mental connections, was a challenge for me. The need to connect the message implied by an image to my choice of editing options sometimes confounded me. I realized that I needed to examine this important habit or I might continue to have difficulty connecting with my audience. In their book, New Media Design, Austin and Doust emphasize the importance of graphic design choices and that

no matter how important the message is, people won’t give it a second thought unless it is presented in a way that captivates and engages them” (116).

I learned that subtlety (or at least simplicity) is often the best path for beginners in all aspects of graphic design composition. I eventually gathered sufficient confidence and resources while creating my Image Project with Photoshop Express to create an information wiki for beginners. I learned through the creative process that although new media allows us “to choose from the hundreds of possibilities of thought, feeling, action, and reaction and to put these together in a unique response, expression or message”(quote from poet Clarissa Pinkola Estes) it still must ultimately connect with the intended audience to produce meaning.

Even when the audience is clearly defined, using multiple mediums and design elements can still cause a project to become unfocused. My class Video Project is a case in point. This project, created on Windows Movie Maker, was the most challenging for me because it required the coordination of visual and audio elements. I spent hours just timing the Free Music Archive track to coordinate with the still images in my project. Rereading Jeanne Verdoux’s description of the creative process (Austin and Doust 43), pen, paper, and hundreds of storyboard images, reminds me of how impatient I can become when working on even a simple computer design project consisting of only twelve images. But Persistence is a habit of mind that I’ve acquired over my lifetime by believing in my ability to succeed at most anything I seriously attempt. The desire to succeed at learning these new technologies energized my creative process.

An additional challenge to a multimedia composition is the huge amount of free software and image sites available that leads one to forget that images, music, and archived written material, are authored by an individual or group entity that often has ownership rights. I learned during this project just how complex (albeit nebulous) citing electronic media ethically can be compared to the familiar MLA style citations I use as an English major writing traditional academic papers.

As I completed my final project, a hypothetical class website, I reflected on comments I had received on my blog from fellow classmates during the semester and how inter-connected computer technology has allowed us to become. My website connected to my blog, to outside resources, and to documents in shared files that created an unending web of information and community. Englebart describes his vision of “reaching the point where we can do all of our work on line” and the computer becomes an extension of ourselves, what he calls “man-computer interaction” (234). When I’m communicating by using a computer though I’m not interacting “with” the computer but with people, so as a teacher Responsibility is a habit of mind that I take very seriously. Being accountable to one’s students is the highest responsibility of a teacher. In the case of a class website, it became not only my desire to communicate, but my responsibility to provide information clearly, concisely, and ethically. The C.R.A.P. design principles:

- Contrast

- Repetition

- Alignment

- Proximity

provided the guidelines to accomplish my task. The end result was a clear, user-friendly network of hyperlinks to course documents, outside resources, interactive pages, and shared calendars. Deleuze and Guattari, in their article “A Thousand Plateaus,” written twelve years later, use the metaphor of a rhizome to describe and expand on the complex structure of Engelbart’s vision. Unlike a tree, that has one trunk with many roots, a rhizome is a bulb-like structure that although connected to the whole, is itself a complete unit (hierarchy) “a map that is always detachable, connectable, reversible, [and] modifiable” (409). This is the essence of a thoughtfully designed website, something only imagined when these articles were written in the 1970’s and 80’s. Flexibility the habit of mind that allows one to adapt as needed is a valuable personal asset and the very essence of hypertext theory. I don’t believe that I would have had the success I did this semester (and retained my sanity) without the ability to be flexible even to the extent of an occasional about-face.

Cited:

Austin, Tricia, and Richard Doust. New Media Design. London: Laurence King, 2004. Print.

Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA), National Council of Teachers of English(NCTE), & National Writing Project (NWP). (2011). Framework for success in postsecondary writing. Retrieved from http://wpacouncil.org/framework

Wardrip-Fruin, Noah and Nick Montfort, eds. The New Media Reader.Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattaro. From “A Thousand Plateaus.” Wardrip-Fruin and Montfort 407-409.

Engelbart, Douglas and William English. “A Research Center for Augmenting Human Intellect.” Wardrip-Fruin and Montfort 233-246.

McLuhan, Marshal. “The Medium is the Message.” Wardrip-Fruin and Montfort 203-209.

Cover Letter for Hypertext Project

Here’s the link to my first Hypertext Website Project

Topic and Purpose of Website

My first website is a prototype for a hypothetical first-year composition class called Practical Writing. I envision this class as a useful addition to a Community College two-year technical or associate degree program where good written communication skills rather than academic writing are stressed. My audience is the approximately fifty percent of Community College students, according to CollegeBoard.org who do not plan to transfer to a four-year college, but still need good, transferable writing skills. I also plan to use many of the design ideas I learned during this process to create an actual class website for an independent study I’ll be doing this summer.

Design and Development Process (C.R.A.P.)

I love color, and lots of it. This, in combination with a naturally eclectic design sense, was bound to lead to many hours of site editing. I realized that I had crossed the line of good design practices when, prior to reading the C.R.A.P. articles (even though I had removed my brightly colored home page image), I received the following comments from my fellow classmates; “Even though the color scheme is one you don’t see often (black/red & blue/yellow), it works surprisingly well.” Another classmate wrote, “The red on you project is very bold.” I took these suggestions as kindly hedged constructive criticisms, and scrapped my original brightly colored Home page image for a more “subtle” bright red on white image. Now my Home Page had a huge amount of white space for contrast, but it wasn’t an audience grabber. So, after weeks of playing with the new image, I switched it back to my original choice; I’m happy I did too. I chose to create contrast on my homepage by using color mainly as a frame around large areas of white space. I think my choice of bright contrast exudes energy, creativity, and warmth― just the feeling I want for my class. I like how the bright image draws attention to the count-down calendar gadget too. I realized that color could be overwhelming though if it distracted from my focal points, so I opted for changing most of my script to black, using font size and bold lettering to draw attention where needed. In my sidebar, I used a dark shade of gray for the text so as not to compete with the black text of my page content, and I kept a touch of red too. Another eye-catching move I made was to use the turquoise color of my background for all my hyperlinks. All title fonts on the site are Verdana (except for the main site font which is Asset), and all text font is Trebuchet.

The page I had the most trouble with was the Assignment page. There was a lot of information that I wanted to appear here. One classmate confirmed what I already suspected, that “on [my] “Assignments” page, some of the assignment titles are gray and are the links, while the ones that are not links are black. Visually, it is distracting.” Another classmate mentioned “that the font size on the Assignments page is a bit large to read and is inconsistent with the rest of the site.” I really cleaned up this page (and standardized the fonts overall on the site). I used a simple image of a blank notebook, a small font size for the text, red and bold for the main instructions, gray for all assignments, and underline for all links, which created the proper hierarchy of the information and assignments, as well as providing good repetition of design element with the other pages. I used a line to separate each assignment. Only the first two links are operable at this time.

The Instructor’s Page uses my photo to connect (proximity) the two personal aspects of this page together; How to Contact Me and About Me(Do you like how I went all the way to France with my turquoise shirt just to create repetition of color on my website?) This page also serves another practical purpose. Students will also use this page to make appointments with me for conferences on a shared calendar (not the one that’s there now). This is the only page where I used a totally different font (Normal in italics) to make a special point― to mind my privacy when calling my home phone.

The Class Newsletter page is a template for a monthly student-edited project utilizing peer-review as its means of success. Students will write original newspaper-style articles, ads, haikus, and profiles of people in the news here on a rotating basis as part of their course grade. I hope that this newsletter would work entirely as a peer reviewed project. I aligned the image slightly outside the page boundary to suggest its impermanence as part of the Class Newsletter page.

The Student Page contains a limited amount of pertinent resources to ensure success in the course. My rational is that students will be more likely to use resources if there are only a few of them. Because of the limited amount of text on the page, I experimented with an asymmetrical balance layout that I learned in Basics of Design: layout & typography for beginners to create flow around the page. Rather than use a stock image on this page, I used a Wordle of the information on the page. Wordles might be a fun resource for students to use as a way of drawing important points from class readings. This, for instance, is a Wordle of the first portion of the article “Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework” by Douglas Engelbart from our class textbook.

Habits of Mind, one of the subpages to the Student Page, is just the draft from the WPA Council. Ideally, this page will be constructed to link out to explanations and resources for specific habits of mind that are pertinent to the student. The class syllabus is the second subpage of the Student Page. Rather than make this a primary page, I note at the top of the page that any changes to the syllabus will be in the Announcements section of the Home Page.

Learning Process

I began the learning process for this project feeling very insecure and by taking notes on various tutorials.

- FollowMolly.com

- YouTube video

- Two student Webinars

- Basics of Design: layout & typography for beginners. 2nd ed.

In the end though, I dove in, made mistakes, resolved numerous hopelessly unorganized elements, and emerged with an acceptable, finished product. Oddly enough, the finished product looks nothing like I wrote about in my first blog about the project. My “calming colors” evolved into a blaze of vibrancy. My audience changed too, from “undergraduate writing students learning about multimedia text construction” to community college non-transfer students learning practical written communication skills. What I learned is that I’m by nature a changeable (flexible), persistent, and independent person. These characteristics generally serve me well, but they often lead me to take a rougher road than necessary and that sometimes leads me to dead ends. In the future, I will benefit from taking a more systematic approach, fleshing out my outline better, and referring back to the many things I learned this time around. I would like to learn how to lay out grids more effectively to “both divide and unite the page” (Austin and Doust 65).

Scholarly Discussion

Various authors describe and expand on the C.R.A.P. guidelines. New Media Design expands on these guidelines by adding sound and movement to the design process while “[relying] on rules to create a sense of the whole” (Austin and Doust 71). I reflected that self-discipline, structure, or the inevitability of following the rules, is something that evolves as knowledge and experience is acquired and broadened. After some initial wild scurrying about my fragmented site, I started following new rules that create structure in hypertext and found, like Douglas Engelbart, in his article “Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework,” that “when I learned to work with the structures and manipulation processes . . . that I got rather impatient if I had to go back to dealing with . . . books and journals, or other ordinary means of communicating” (Wardrip-Fruin and Montfort 107). My messy process eventually coalesced from a learning experience for me to a product that could contribute to the learning of others (which was Englebart’s goal too). When Theodor H. Nelson broke down the writing process, he translated the needs of writers into a structure too. That structure allowed for movement and “various provisions for change” into “any form and arrangement desired” (137).

Bibliographic Information for Site Links and Learning Resources

Austin, Tricia, and Richard Doust. New Media Design. London: Laurence King, 2004. Print.

Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA), National Council of Teachers of English(NCTE), & National Writing Project (NWP). (2011). Framework for success in postsecondary writing. Retrieved from http://wpacouncil.org/framework

Darling, Dr. Charles. Darling’s Guide to Grammar and Writing. Capital Community College Foundation. Web. 11 April 2012. http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/

Graham, Lisa. Basics of Design: layout and typography for beginners. 2nd ed. London: Cengage, 2005. Print.

Old Dominion University’s Academic Skills Unit- http://uc.odu.edu/academicskills/

Old Dominion University’s Perry Library-http://www.lib.odu.edu/

Steves, Rick.Rick Steves: Europe through the Back Door. N.p., Web.11 April 2012. http://www.ricksteves.com/

Tidewater Striders Running Club. http://tidewaterstriders.com/

Wardrip-Fruin, Noah and Nick Montfort, eds. The New Media Reader. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003. Print.

Engelbart, Douglas. “Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework.” Wardrip-Fruin and Montfort 95-108.

Nelson, Theodor H. “A File Structure for the Complex, the Changing, and the Indeterminate.” Wardrip- Fruin and Montfort 134-145.

Wordle “word clouds”. http://www.wordle.net/

You must be logged in to post a comment.